- Home

- Georges Hormuz Sada

Saddam's Secrets Page 17

Saddam's Secrets Read online

Page 17

He said, “Is it going to be substantially different from the presentation we’ve just heard from the air force?” At that point I knew Shanshal understood that everything Muzahim’s spokesman had said was ridiculous. So I said, “Yes, sir, it’s 180 degrees different.”

Gen. Shanshal said, “Yes, okay, Georges. Please go ahead.” So I stood up and walked to the front of the room. As I looked at each of the men seated around the table, I said, “I want to give you this presentation because I was ordered to do an analysis to find out the answers to three questions. First, what is the capability of the enemy air force? Second, what is the destructive capability and accuracy of their cruise missiles? And third, what is the operational capability of the five aircraft carriers stationed in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea? And I want you to know that the information I will share with you now has been provided to me by Gen. Sabir, who, as you all know, is commander of the intelligence service of the military.”

I realized that if I were to give these officers my assessment based only on my own knowledge, they wouldn’t believe it and they wouldn’t trust me. But if I let them know that everything I’d discovered was based on information I’d been given by our intelligence officers, then they would know it wasn’t just my opinion but the official assessment of our best military analysts.

When I began, I decided I would use the same examples that Gen. Muzahim had used. The first was fourteen aircraft coming from the west to target Iraq. According to the air force’s presentation, all fourteen would be destroyed. How? He said 25 percent would be shot down in air-to-air combat, 25 percent would be shot down by surface-to-air missiles, 25 percent would be destroyed by anti-aircraft defenses, and only two would make it into Iraqi air space, and they wouldn’t be able to acquire targets because of the flack and anti-aircraft fire in the air. So the result was no damage done.

My analysis was somewhat different. I said, “Of the fourteen aircraft in the example we’ve just heard, I can assure you that all fourteen will be able to penetrate our borders and carry out their strikes successfully. Why? Because these fighters will not be the first to come across. They will only come after the missiles have taken out the key targets. In addition, these aircraft will have support from AWACS Sentries overhead, giving them a detailed map of exactly what’s happening on the ground and in the air around them, so they can maneuver and avoid hot spots.

“Many of them,” I continued, “will be carrying HARM missiles. These weapons are designed to target radar. Which means that as soon as they detect a radar signal from any direction, they can follow the pulse of the radar to the point of origin and destroy the tracking station. And even if the technicians were to switch the radar off, the coordinates of the installation will already have been stored in the missile’s computerized memory, and it will continue to its target and destroy it.

“Furthermore,” I continued, “when these fourteen aircraft have destroyed our tracking radar, the Iraqi fighters will be unable to scramble because, for all practical purposes, they will be blind. They will have no way of seeing the enemy aircraft they’re expected to engage until it’s too late.

“Any Iraqi fighter that engages in air-to-air combat under those circumstances,” I said, “will be a sitting duck for coalition pilots. They won’t have a chance. You should also know that the American Tomcat fighters have a forward-scanning radar with a range of more than 150 miles, while our best scanning radar can see no more than 15 miles ahead. And the Tomcat has the capability of scanning twenty-four targets at a time, and then firing on six targets simultaneously with pinpoint accuracy. If the coalition aircraft go up,” I told them, “they will penetrate our borders. And if they penetrate our borders, you can be sure they will hit their targets.”

A War of Words

When I paused for questions, I could see that nobody liked what I’d said. One of them, who was chief of staff of the army, growled at me, “Georges, are you trying to frighten us?” I said, “No, sir. I’m not trying to frighten you. I’m telling you the truth according to the best of my knowledge.” He hadn’t expected anyone to answer him back; these men were accustomed to intimidating people with their outbursts. But I was certain we were going to be attacked, and it would have been immoral not to warn them. So I persisted.

Since there were no more questions, I decided to talk about a topic that had often been mentioned by Saddam. He had said many times that, more than anything, he wanted to destroy an American aircraft carrier. He didn’t have any idea how difficult that would be, but Saddam was never dissuaded by facts. The chances of our getting anywhere within striking distance of a U.S. carrier were non-existent. Unfortunately, some of our commanders thought of an aircraft carrier the way they thought of a fishing boat. They had no idea that a carrier is, in fact, a floating city—a heavily armed and dangerous floating city.

But when I explained what a carrier can do, its size, the armaments of the warships that accompany it, and all the weapons she could carry, most of these men were amazed. I told them, “If you want to attack an aircraft carrier, you’ll have to send at least ninety-seven fighter jets against it, knowing that ninety-six of them will be destroyed before they get close.” I had said the same thing to Saddam in a previous briefing—that we could lose as many as ninety-six fighters for the slight chance that one might get through—and he was ready to do it anyway, even at the cost of so many lives. That was how much he cared about his men.

As I continued, I told the generals that when a carrier’s radar detects an enemy aircraft coming from a certain direction, the captain can initiate an automatic weapons release program that will detect incoming rockets and destroy them in flight, from sea level up to three thousand feet above the surface. By contrast, our best rocket, the Exocet missile, was not very large, and even if one of them were to hit the armored shoulder of an American carrier, it would have about as much effect as a house fly scratching the shoulder of an elephant.

This made Gen. Hussein al-Rashid, who was a relative of Saddam, very angry. He scowled at me and said, “Okay, Georges. What’s the solution? What are we going to do?” I said, “The solution is very simple. We sent the army into Kuwait with a piece of paper and we can bring them back out with a piece of paper. President Bush said that if we withdraw our forces before January 15, nothing will happen.” And then I added, “Unless we’re prepared to go to war with America, we should order our forces to withdraw immediately.”

The minute I said that, it was like a bomb had gone off in the room. Somebody yelled at me, “Georges, you’ve said that one time, but if you ever say it again your head will be separated from your body!” I said, “For God’s sake, let my head be separated from my body, but at least let my nation live! If we insist on staying in Kuwait, believe me, this country will be destroyed.” Everybody heard what I said, and to this day they remember it. Many of the men in the room that day are dead now, and many more are incarcerated, awaiting their trials. But in their prison cells, I’m sure they hear my words echoing in their minds again and again, because I was speaking the truth, and they all knew it.

Nevertheless, someone said, “Okay, Georges. We hear you, but we want you to stop now.” So I stopped. Gen. Muzahim looked at me and said, “Georges, I don’t know why you always have to speak this way. Your words are so harsh; can’t you speak words that are a little softer?” I said, “No, sir. I cannot speak softer. It’s the other way around. As much as we’re able, we ought to explain our situation to the people of Iraq, because I’m not making these things up. Everything I’ve told you is the truth, and you know it. This is precisely what’s going to happen if we don’t withdraw our soldiers now.”

I could see that he wanted to end the conversation, but I added, “General, you have an army of a million men, and they’re all deployed in the south, either in Kuwait, Basra, or other places. And these are the boys who are going to take the brunt of it when the Americans come. As generals, the least we can do is tell them the truth.” But Gen. Muzahi

m wasn’t listening anymore. In his head, much like Saddam, he was convinced the attack would never come.

Selective Amnesia

Before going to that meeting, I had prayed silently, God, please help me to speak plainly and tell the truth. I will tell them everything, and then I will gladly accept whatever happens to me. The thought of lying to our troops, lying to our pilots, and lying to the nation was more than I could stand. It was as if all our commanders had selective amnesia. If nobody was willing to stand up and speak the truth, then there was no hope for us. I’m convinced God heard that prayer, and he gave me the courage to say it. On my own, I’m not that brave. It’s not easy to swim against the current when everyone else is pretending that everything is going to be okay.

I’d been brought back out of retirement and put back in uniform on the grounds that I was to observe and advise the general staff on everything, but I was told I would have no command authority. I was not a member of the party like everyone else in the room. So how was I chosen to speak about things no one else dared to address? I don’t know that anything like it had ever happened in Iraq before that day. But as I stood there in that room, I realized that I’d been given a very special privilege, and I was determined to fulfill my duty with honor.

There’s a saying in Arabic, “Don’t be a mute Satan.” It means, if you have important information that may help someone in a difficult situation, say something. Don’t be a devil and keep silent when you can say something to help. And you know, if I’d failed to warn them about the risks to our military, they would certainly remember after the invasion, and then they could come to me and say, “Georges, why didn’t you tell us what you knew?” They didn’t like what I had to say that day, but they could never accuse me of keeping my mouth shut when I knew that all our armed forces would be at risk.

I’m convinced it was Jesus who gave me the courage to say what I had to say. And today everyone knows that when the time came to speak, only one man told them the truth, because the invasion did come and everything happened just as I’d said it would. But there were two big problems with their way of thinking. First, Saddam had spread the idea that we didn’t have to worry because nobody was going to attack us. But it was also because, as I’ve said repeatedly, when Saddam wanted two plus two to be nine, then they would gladly say it was nine.

I didn’t do that, and I didn’t stop with my assessment of the air war. I also told them about the aircraft carriers, the cruise missiles, the long-range artillery, and all the other weapons that the Americans could use against us. And in the middle of this, Gen. Al-Rashid interrupted me again and said, “Georges, don’t you think that you’re exaggerating the capabilities of the Americans and the accuracy of their weapons?”

The question made me angry and I didn’t have any respect for this man. He was younger than I was and he’d been given higher rank simply because he was a relative of Saddam. So when I answered him, I didn’t call him “sir.” I just said, “No, I’m not exaggerating. What I’ve told you is exactly correct. This is the capability of the weapons, and believe me, the coalition forces know how to use them.” I knew what was going to happen just three days from that day, so there was no need to be polite. But I said to everyone in the room, “If you have any other questions, I will be happy to answer them.” But there were no more questions.

Before we left the room, I told them one more thing. I said, “I want you to know that everything I’ve told you is from the intelligence given to me by my brother, Gen. Sabir, the head of military intelligence.” Gen. Sabir was sitting there quietly, so I looked over at him, but he didn’t say a word. He knew that what I had said was correct.

Removing the Impediment

There was to be another meeting on January 14, one day before the deadline set by the United Nations, and this time it was to be in Saddam’s operations room. He had sent orders that all the field commanders were to be there, and we were supposed to do our presentations for him. This would be the last presentation before the action deadline.

But as I was preparing my remarks the night before, I received a phone call from the air force headquarters, and they said President Saddam had chosen me for a special mission. I was to fly to Mosul on the morning of the fourteenth to make a presentation to the Jordanian pilots who had joined the joint fighter squadron. They were being called back to their bases and were preparing to leave Iraq that day to return home to Amman.

About a year earlier, Jordan and Iraq had reached an agreement to create a series of national squadrons—meaning, basically, that they were to be defenders of the “Arab nations.” The plan was for each squadron to be made up of ten Iraqi pilots and ten Jordanians. The aircraft would be Iraqi, but the pilots would come from both countries. At that time we had two of these squadrons, but on the evening of the thirteenth, King Hussein ordered a C-130 Hercules transport to be sent from Jordan to pick up his pilots and bring them home the next day. For me, this was one more indication that something big was about to happen.

King Hussein had always maintained close ties with the West, and he knew what was coming. He didn’t want his young pilots to be in harm’s way, and that’s why he ordered them to return home immediately. This only made my suspicions of an imminent attack that much more certain. The king obviously knew something that Saddam didn’t know, or didn’t want to believe. In the meantime, I was told, Saddam had decided that he wanted me to go and meet the pilots before they departed. I was to thank them for their service in Iraq, and then to present each one with a handsome new pistol—a special gift from President Saddam. When they called me from the command center, they said that Saddam had told them, “I need one good, high-ranking officer to go and represent me.”

They said I would be taken in Saddam’s personal airplane, which was a nine-passenger JetStar with all the most luxurious amenities. Saddam’s Republican Flight Command maintained four aircraft that were used solely by the president. But at Saddam’s order, they sent a car to drive me to the airfield. When I got to Saddam’s four-engine plane sitting on the tarmac, they said, “Gen. Sada, you are the obvious one to take these pistols and make the presentations to the pilots.” And they loaded on-board the boxes containing all those weapons, in the passenger section.

I was glad to take the twenty pistols and present them to the Jordanian pilots, but I was disappointed that I wouldn’t be there for the big presentation to Saddam. I was anxious to do my presentation because I had put together three large files covering the issues I’d been researching for several months. But it was obvious that the army and air force commanders didn’t want me to be there because they knew I would tell Saddam the truth. I’d have to say that two plus two is four, and that’s the last thing they wanted him to hear.

So I made the trip to Mosul and I took with me one of my former students, Staff Colonel Riadh Abdul Majid al-Tikriti, who happened to be from Tikrit. In fact, he was a relative of Saddam, but I told him that I didn’t want to go to Mosul alone and it would be good if he would accompany me. He would have a chance to meet the pilots when I made the official presentations before they boarded their aircraft and headed back to Amman. So that’s what we did. We flew there, met the pilots, and had a nice dinner. The base commander had arranged a big farewell dinner for the Jordanians, and that’s where I made the presentations. I thanked them on behalf of the president for the year they’d spent with us in the new national squadron program. Then, afterward, they boarded their C-130 and left.

A Return to Reality

When I got back to Baghdad, I went straight to the operations room at headquarters. As soon as I walked in, several of the young officers pulled me aside and said, “Gen. Sada, the meeting with Saddam was much worse than the one you attended on the twelfth. They lied to him even more than before, and no one dared say a word.”

They had even told Saddam that our technicians had modified a large number of surface-to-surface rockets to make them capable of surface-to-air strikes on the American AWACS and B-117

Stealth aircraft. Of course, this was absolutely absurd. There were no weapons in our arsenal that could come close to either one of those high-altitude aircraft. But this was the time when Saddam went on national TV and told the people, “No Iraqi needs to be afraid of ‘Stealth’ airplanes. We have the weapons to destroy them.”

I asked the officers, “Who did that?” and they told me it was Gen. Yaseen. So I went to see that man and I asked him, “General Yaseen, can you please explain to me how you plan to destroy the AWACS Sentry aircraft and B-117 Stealth bombers capable of flying at more than thirty thousand feet with your modified surface-to-air rockets?”

Of course, he couldn’t answer me, and he didn’t try. This was a lie concocted for the benefit of Saddam. So instead of answering, he said, “Georges, why are you always so negative? They all loved my presentation, and President Saddam was very happy with the things I told him.” I just shook my head and left the room. This was the mentality of the people whom Saddam had surrounded himself with.

I was certain it was only a matter of time until we would be hit by rockets and missiles, as well as many other weapons the coalition aircraft could throw at us. I was sure of it. But the fifteenth came and went, and nothing happened. I must say, I was more than a little bit surprised. The next day it appeared that I had been wrong, and by that time everybody in the air force was laughing at me. Some of the officers who had been at the briefings where I had spoken so forcefully began making fun of me: “Georges, you told us we’d be hit by the Americans, didn’t you? Where are the bombs, General?”

Some of the officers started calling me General Catalog, because I had all the facts and figures, like a catalog, and they knew I didn’t like to go into any operation without a wide assortment of substantial and reliable intelligence data. Of course, I was embarrassed that I had spoken so confidently about the impending attack by the Americans when, in fact, nothing happened. I was beginning to look foolish to everyone, and I was feeling very bad about it.

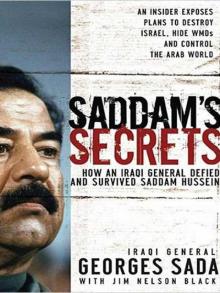

Saddam's Secrets

Saddam's Secrets