- Home

- Georges Hormuz Sada

Saddam's Secrets Page 2

Saddam's Secrets Read online

Page 2

Saddam’s eyes were threatening, but he knew what I meant. What I was asking for was a centuries-old tradition among the desert Arabs, an oath sworn by tribal leaders to allow a messenger to speak freely without fear of being killed. As he folded his arms across his chest, Saddam said, “Yes, I give you immunity.” Then, more forcefully, he said, “Now tell me what you mean!” I had no choice but to answer him. I knew full well that he had given immunity to others in the same circumstances and they were hanged, but I was honor-bound to tell the truth. So I breathed a silent prayer, Lord, give me the courage to speak, and I spoke.

From beginning to end, my answer took one hour and forty-one minutes. When I served as air vice marshal in the air force, I studied all these things in detail, so I had extensive knowledge of the military capabilities of the forces in our region, as well as those in Europe and North America. So I was able to cover those topics in detail. But the minute I finished, Saddam erupted once again in anger. Fortunately, this time the anger wasn’t directed at me but at the others who had not told him the truth about these things.

Most of these men were eager to assure Saddam that two plus two is nine, because they knew that’s what he wanted to hear. But, thank God, Saddam listened to me, and that was a miracle in itself. He never listened to anyone. He had his own ideas and he never wanted to be confronted by the facts if they would prevent him from doing whatever he had already decided to do.

When I told Saddam that attacking Israel would be like the blind attacking the sighted, we were surrounded by all of the members of the general staff, and Gen. Amir Rashid Ubaidi, who was deputy air force commander for technology and engineering, leaned over to his colleague and whispered, “Georges is going to be killed, now, right on the spot. His head will be separated from his body.” I didn’t hear the remark, but they told me later what he’d said.

Gen. Amir, incidentally, was a true genius. He had been number one in his class at the University of London, where he earned his Ph.D. in engineering. After the Gulf War, he was taken into custody by the Americans and imprisoned in Iraq. He had been in charge of the “superweapons” program but claimed that Iraq never had chemical weapons or WMDs of any kind; of course that wasn’t true and he, of all people, knew it.

In any event, I told Saddam that the reason I had used that expression is because Israeli aircraft have very advanced radar with the capability to see more than 125 miles in any direction. On the other hand, 75 percent of Iraqi aircraft were Russian-made, and the range of the radar on our fighters was only about fifteen miles. This meant that the Israeli fighters could see our aircraft at least 110 miles before we would even know they were there. And that’s not even the worst part. Their laser-guided missiles could lock on our fighters while they were still sixty-five miles away, and we’d have no idea that enemy fighters were anywhere around. Then the Israeli pilots could fire their missiles at a range of at least fifty miles and our pilots would never even know what hit them.

So at that point I asked Saddam, “Sir, don’t you agree that this is a fight between men who are blind and men who can see?” Saddam just sat there for several seconds looking straight ahead. Then he turned sharply to his left where Gen. Amir was sitting and he yelled very loudly, “Amir, what is Georges saying?” In other words, Saddam was asking his weapons expert: Why haven’t you told me this before now? This is your area, and I hold you personally responsible for telling me these things.

I didn’t change my expression but continued to look at Saddam. But then I realized, Oh, no! Gen. Amir is not that brave. I’m afraid he will not tell Saddam the truth, and he’ll try to put the blame on me or someone else. So I turned quickly and looked Amir straight in the eye, and he could see that I was very serious. After the meeting he came to me and said, “I knew, Georges, when you turned to look at me that way that you were sending a message.” And that’s exactly what I was doing. Without saying a word I was telling him to speak the truth because we were both speaking directly to Saddam Hussein. If he disagreed with me or tried to lie his way out of it, I would have defended myself in the strongest terms, and Gen. Amir knew exactly what I meant.

Well, God was with me that day because Gen. Amir said to Saddam, “Sir, what Brother Georges is saying about the difference between the Israeli aircraft with sophisticated American and European technology, and our Russian-made aircraft with Russian technology, which is not so sophisticated, is right.” And then he began explaining it to him in very detailed engineering terms, telling Saddam everything about the technology of the different fighter aircraft. Amir knew that Saddam didn’t care in the least about any of those details; he was just covering his own backside. But what it came down to was that he told him, Brother Georges has told you the truth about our fighters, and we’re no match for the Israelis.

When he finished, Saddam just sat there, silently, staring straight ahead. For more than a minute you could have heard a pin drop in that room. And, believe me, a minute of silence in the presence of Saddam Hussein could seem like eternity. There were at least ninety people in the room, all generals and high-ranking commanders, and there wasn’t a peep out of them.

At the end of the meeting, the only thing I could be sure of was that Saddam had listened to me, and he knew that to the best of my ability I had told him the truth. I had no idea what decision he would make, but at least he had heard me and he understood what I’d said. Then in mid-December 1990, less than a month from the deadline that had been set by the United Nations for Saddam to pull our forces out of Kuwait, I was told that the president was ready to announce his decision.

On December 17, we received the message we’d been expecting. Saddam’s message was worded very deliberately, almost poetically in Arabic, to give the impression of a decree of great solemnity and importance. It said, “Uwafiq Tunafath Ala Barakatalah,” which means roughly, “I agree to the attack, and we shall attack with the blessings of Allah.” It was as if Nebuchadnezzar had spoken. But what he was saying was that we were being ordered to proceed with a massive chemical-weapons assault on Israel, in two waves, one through Jordan and the other through Syria.

INTRODUCTION

A MAN OF THE PEOPLE

“He was not a man of the people or a friend of the Arab people.

The fact is, Saddam Hussein killed more Arabs than anyone in the history of mankind.

There was nothing he wouldn’t do to secure his grip on the country, and there were no

principles he would not sacrifice

for the sake of his own power and greed.”

In Iraq there was no leader, no general, no commander, no minister. There was only one man who claimed to be all things to all people, and his name was Saddam Hussein. During the dictator’s thirty-five-year reign of terror, he transformed Iraq into a very small country—from twenty-seven million hard-working men and women to just one man.

And just imagine how this tyrant dominated everything in our lives: Saddam and the army, Saddam and the Party, Saddam and the Republican Guard, Saddam and the special guards, Saddam and the tribes, Saddam and the people, Saddam and the rivalries in the Middle East, even Saddam and religion, when he was anything but a religious man.

Saddam manipulated all of these groups, constantly playing one against the other, in order to expand his grasp and control over the region. His ego was so enormous he never even realized how ridiculous he looked to everyone else. Emotionally, Saddam was a child with a disturbed personality, totally focused on his own power and glory. If he hadn’t been stopped by the grace of God and overwhelming military force, believe me, Saddam would not have been satisfied with Iraq alone. He would have used his ever-increasing power to turn the whole world upside down.

When the American-led coalition came back to Iraq in 2003 to liberate my country from the grasp of Saddam, they did us a great service. They were able to rout the enemies of freedom and destroy Saddam’s corrupt regime by going after the leaders of the Baath Socialist Party. But they also took pains not to ta

rget the civilian population or destroy the infrastructure we needed so badly. During Operation Desert Storm in 1991, 147 bridges were demolished by coalition bombers and missile strikes. In 2003, by contrast, not a single bridge was destroyed.

Unfortunately, not everyone understands or appreciates what happened. Some people, both in the West and the Middle East, were strongly opposed to the decision to use military force against Saddam. But I’m not one of them. I believe it was the only thing that could have saved Iraq from utter ruin. Saddam’s paranoia and lust for power were consuming everything and everyone, and no one was safe so long as he remained at large. Most people in my country are beginning to see that now, as they realize how things have changed since Saddam was driven out. And now that the liberation of Iraq is a fact, many who resisted in the past are beginning to say, “Okay, I guess they did the right thing after all, because things are so much better now.”

A Unique Perspective

As an Iraqi pilot and ultimately as an air vice marshal of the air force, I have spent most of my life serving my country. My connection to this place is real and very deep. I am an Assyrian Christian, born and raised in northern Iraq, and a descendant of the original inhabitants of this ancient land. My people were making a living from the mountains, rivers, and fertile plains of the Tigris and Euphrates Valley long before Abraham made his historic journey from Ur of the Chaldees to the land of Canaan.

My ancestors were living in the ancient capital of Nineveh when Jonah arrived, having been sent by God to call our pagan forebears to repentance. At that time, Nineveh was the capital of the Assyrian Empire. The armies of Assyria were led by warrior kings with strange-sounding names such as Shalmaneser, Tiglath-Pileser, Sargon, and Sennacherib, and they conquered much of the ancient world, destroying the nation of Israel five separate times.

The people of Assyria worshiped the gods of nature, but they did not know God. So God sent Jonah to tell them to repent, or else he would destroy the city as he had done to Sodom and Gomorrah. The Bible also says there were 120,000 people living at Nineveh, with all their cattle and livestock. It was a three-day journey to walk from one side of the city to the other. Jonah cried out for the people to repent, and when the king heard it he put on sackcloth and sat in the ashes. He commanded the people of the nation to fast and seek the face of God. So in the eighth century BC, the people of Nineveh repented and turned to the God of the Bible.

To this day we still celebrate a three-day fast called Bautha d’Ninweh, meaning the Fast of Nineveh. It’s held each year three weeks prior to the first day of Lent and about nine weeks before the Easter celebration. In ancient times, the people did not eat or drink at all for three days. The Bible says the king of Assyria commanded that not even the cattle or livestock were to be fed during the fast. Today, however, we understand that the fast is symbolic and it is a way of recognizing our need for repentance and faithfulness to God.

Traces of that legendary city survive to this day. The modern Ninawa faces the city of Mosul in the province of Ninawa where I grew up. This “land between the rivers” known as Mesopotamia was once the home of Sumerians, Akkadians, Assyrians, and Babylonians. For more than seven thousand years our ancestors dominated the region, and they enjoyed a rich and thriving commerce that spanned the known world. And believe me, all this history still lives in the hearts of our people.

Like every ancient society, we’ve seen many wars. Under a succession of warrior kings, the empire expanded and contracted based on military conquest and its legendary trading caravans. In the time of Alexander the Great, the Assyrian legions formed the right wing of the Persian Army, and they fought like lions. Soldiers of the Assyrian Empire, which had fallen in 612 BC, fought with the Persians against Alexander. If the empire hadn’t fallen, I suspect we would have sided with Alexander against the Persians. But such is history. Alexander died in 323 BC, near the city of Babylon in southern Iraq, but that would not be the end of conflict.

Christianity came to the region in the first century AD with St. Thomas, the disciple of Jesus, who passed through Mesopotamia on his journey to India. Subsequently, others were converted by Saint Addai and Saint Mari, who were also missionaries in the first century. These early converts included many from the Jewish Diaspora, and Iraq remained predominantly Christian until the Arab Conquest of 634 AD when Islam was imposed as the official state religion. In time, Islam would become the dominant religion of the entire region, and Arabic would become the common language.

Even so, not everyone converted to Islam. Today between 3 and 4 percent of Iraqis are Christians. Catholics in Iraq are generally known as “Chaldeans,” while most Protestants are affiliated with denominations such as Presbyterian, Baptist, and Methodist, as well as the Ancient Church of the East, which is comparable to the Orthodox Church. All these people speak Arabic, and many speak other languages as well. The common language among my own people is Aramaic, which is the language of the New Testament—the same idiom that Jesus spoke. When I read my Bible today, I’m reading the very words that Jesus used.

Baghdad was founded as the Arab capital in 762 AD, and it served as the seat of the Abbassid Caliphate from 750 AD to 1258. The Abbassids were defeated by the Mongols under Hulagu, the grandson of Genghis Khan, who left the country in ruins. By the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Iraq was a perpetual battleground of the Ottoman Turks and Persians.

The Ottomans controlled Mesopotamia until the First World War when the British occupied the region and modern-day Turkey was established. Iraq remained a British Mandate until 1932; however, in 1921 the League of Nations and the British government named King Faisal I, a member of the royal Hashemite family, as the nation’s leader.

King Faisal I was responsible for opening up Iraq to Europe and the West, and even after the Mandate ended, British influence remained strong. But this was an era of turbulent changes in the Arab world. Socialism was now the controlling ideology in Egypt and Syria. King Faisal I died of a heart attack in 1933 and his son and successor, King Ghazi, died in an automobile accident in 1939. Then, in 1958, Ghazi’s son, King Faisal II, was overthrown by a military coup led by Gen. Abdel-Karim Qassem, who transformed Iraq into a pro-Soviet republic.

A Strange Relationship

As fate would have it, I became a cadet in the Air Academy that same year, and the new regime had very different ideas about training its officers. After graduating as a young flyer, I found myself involved in coups, wars, battles, battle-planning, and every other type of military operation that would shape the fate of the nation. So that’s the perspective I bring to this book.

I was involuntarily retired from the air force in 1986, brought back by Saddam after the invasion of Kuwait in 1990, and then imprisoned by Saddam a short time later. I will explain all this in subsequent chapters. But so long as I wore the uniform of my country, I was a loyal soldier and I followed orders. I was a highly trained fighter pilot, educated in Russia, America, Great Britain, and other parts of Europe.

I flew the MiG-17 and the MiG-21, and I had a national reputation as Iraq’s most daring aviator before I had earned the rank of captain. In time I rose to become an air vice marshal, a two-star general, and I was responsible not only for training Iraqi fighter pilots but also teaching courses on air power and military readiness at the War College, the Army Staff College, and the National Defense College.

These were things I was proud of; it’s what I had worked my whole life to achieve. But I was not a member of the Baath Party. As an Assyrian Christian, I would have been a pretty poor candidate. For a long time now I’ve wondered how to tell my story to the American people. How would I explain my decision not to be a member of the Baath Party, and why I refused to be a part of Saddam’s inner circle. In part, it was because I’d been told that the slogan of the party says: “The body of the nation is Arab, and the soul of the nation is Islam.” I was neither Arab nor Muslim and I couldn’t have pretended to be.

For most of my life it has been costly

to speak the truth in Iraq, because the regime demanded that everyone act and think and speak alike. Furthermore, I had a strange relationship with Saddam. It was apparent that he respected me because I was a capable and efficient officer, just as he was in his own way. But I refused to lie for him, and I was honor-bound to speak the truth without inappropriate concern for the political or personal consequences. And I’m sure he hated me for that.

Regardless how people may react, I’m committed to telling the truth, so far as I know it. And I would be dishonest not to be frank about what I’ve done. Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon can’t avoid talking about the fact that he led the Israeli Army’s assault across the canal into Egypt in 1973. It may have been an action that made him less than popular in Palestine and other parts of the Arab world, but it’s still a fact of history. So I, too, will speak candidly about the facts of my own life and career.

During my military service, I was involved in strategic operations, or in the planning of them, in three separate wars with Israel: the Six Day War of 1967, the October War of 1973, and a little-known attack that Saddam wanted the air force to carry out using chemical weapons in 1990. Some of my friends have urged me not to talk about any of this, because it could make some people think less of me.

I’ve been told that people in the West—and especially American Christians who have a close relationship with the people of Israel—would be angry at me because I once fought against the Jewish state. But to deny or simply fail to mention these facts would be less than honest. So in the interest of full disclosure I have chosen to speak fully and openly.

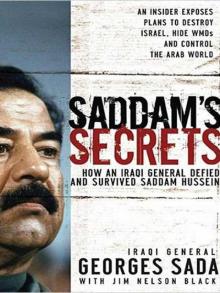

Saddam's Secrets

Saddam's Secrets