- Home

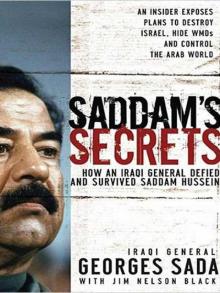

- Georges Hormuz Sada

Saddam's Secrets Page 20

Saddam's Secrets Read online

Page 20

Saddam looked at Muzahim sternly, as if to say, “Why can’t you answer my questions?” Many of our planes sitting on the runways had already been destroyed. If we tried to send up any more, it was very likely they would be destroyed as well. And, of course, that was true. On his way out of the building, Saddam mentioned to me that he had told Gen. Muzahim to call off the attack on Israel. I confirmed this later with Muzahim.

I was saddened by all this because I had done my best and nobody listened. We were attacked from every direction, from north to south. We were hit by F-111 aircraft in the north, by Tomahawk missiles from the Saratoga in the Red Sea, by cruise missiles from the carriers in the Gulf; and we were even hit by the B-117 Stealth bombers from high overhead—it was the first time these virtually invisible bombers had ever been used in actual combat.

I was thinking, My God, what has happened to our country? And I was also sad because when Saddam finally came, hours after the war had started, his first question was why the sirens didn’t go off when the first bombs hit. That was all he could think about. The attacks were still going on, bombs and missiles were falling all over Baghdad, but Saddam wasn’t worried about that. He wanted to know why the sirens hadn’t gone off at the beginning.

But, fortunately, he wasn’t finished yet. After calling off the attack on Israel, he called the army commanders and changed their orders too. Originally, he had wanted to send twelve armored and mechanized divisions into Saudi Arabia, and their orders were to destroy everything in their path for a distance of at least two-hundred miles. From the borders of Kuwait to the city of Dharan, the army was instructed to wipe Saudi Arabia’s industrial zone off the map. He wanted to destroy that complex of high-tech businesses because King Fahd had supported the American invasion and allowed coalition fighters to use his bases.

Scorched Earth

When you understand what Saddam actually had in mind for our Saudi neighbors, you can’t help but see what a madman he was. Saddam was consumed by hatred, and he hated Saudi Arabia even more than he hated the Americans, because the Saudis had helped Kuwait. And in the end they had allowed American fighters to use Saudi bases. So Saddam decided that if he was going to be attacked by America, and possibly defeated, then he wanted to attack Saudi Arabia and do as much damage as possible before he was forced from power.

When he ordered the air force to prepare for the attack on Israel, he ordered an aerial assault on Saudi Arabia at the same time. But this would be different. The attack on Israel was to be carried out by the air force using chemical weapons. The first strike on Saudi Arabia would be carried out by Iraqi aircraft armed with tactical weapons, but it would be followed by a full-scale assault by armored and mechanized infantry. Ground forces were to go in after the air strikes with tanks, armored personnel carriers, and mechanized artillery. And then the air force would make a second strike on the capital, Riyadh—this time with chemical weapons.

The plan was to send twelve divisions of armor and infantry across the border, keeping one division in reserve. They would be going through Kuwait into Saudi Arabia, and he would hold back the reserve forces, safe inside the Iraqi border, to make sure they would be ready to fight when the time came. When he gave the order, they were supposed to go forward in three columns: one column on the highway, one along the coast, and one on the desert side. This was Saddam’s strategy.

They were to cross the border at night and destroy the industrial area between Kuwait and Dharan, which is about two-hundred miles to the south. He was also thinking that we would transfer about 120 aircraft to the two airfields in Kuwait, Al-Sabah and Al-Salim, to provide close air support as these columns moved forward. At the same time there was another plan to send bombers on to Riyadh. The city of Riyadh is divided into two halves. On one side are the king, princes, and aristocrats, and on the other are the common people. Saddam said we didn’t want to destroy the people, just their rulers, but this attack would be done with chemical weapons.

To be sure the plan to drop chemical weapons would actually work, he even had the air force do a series of test drops at the Al Kut Air Base in Iraq. The test weapons didn’t actually contain chemical compounds, but the drop tanks were filled with a material that simulated what would happen. The idea was that in the actual strike on Riyadh an active agent would be added at the last minute, and when the spray was released it would create a toxic cloud that would disperse throughout the city, killing everyone in its path.

This would have been a terrible atrocity if it had happened, but this is what Saddam had in mind for the rulers of Saudi Arabia. Saddam knew there would be a strong reaction to this, but he was unconcerned. After all, he had dropped poison gas on the Kurds in 1983 and 1988 and nothing happened. So he had two Mirage fighters equipped and ready to fly the mission, but both planes were shot down by Saudi fighters at the start of the war before they could carry out their mission.

During the planning stages for the attacks, Saddam had the pilots and support crews brought in to see films showing the layout of Riyadh, where everything was located, both from the air and at ground level. I attended some of those sessions, and they showed films of the massive warehouses used by the Saudis for storage and shipment of parts for military equipment. They had very sophisticated computerized conveyer systems for delivering parts to the right place, and it was very impressive. But Saddam wanted to make sure those warehouses were totally destroyed.

When I learned of the plan, I asked the planners how they were going to carry out such a large operation without the benefit of air cover. I said the air force could provide air support for armor and infantry for about seventy-five miles inside the country but not for the remaining 210 miles to Dharan. The concentration of Saudi and American aircraft at that point would be much too great to go any further. Well, I soon discovered that Saddam couldn’t have cared less about that. As far as he was concerned, it was a suicide mission. In fact, two of our Mirage fighters penetrated the Saudi border and were destroyed by Saudi F-15s, but Saddam wasn’t the least concerned.

He didn’t care if our soldiers or pilots came back alive so long as they destroyed everything in their path on the way to Dharan. And even more diabolical, he wanted Iraq to be destroyed as well. According to his twisted logic, if he was going to be defeated, then he wanted to make sure there would be nothing worth saving after he was gone. And all this was authorized by Saddam on December 17, 1990, on the same sheet of paper on which he wrote in Arabic that we would attack with the blessings of Allah. But, thank God, it never happened, because when we were hit one month later, he realized it was too late, and he cancelled both missions.

A New Assignment

As I had predicted, we weren’t hit by aircraft in the first series of strikes. We were hit by missiles. A good plan of attack would be to strike first with precision missiles in the first wave and knock out radar and communications, damage airfields and runways, and disable the power grid. Then, in the second wave, the plan would be to send in F-117 “Nighthawk” Stealth fighters, which are almost invisible to radar, to hit key military targets and take out the command and control structures. And that’s precisely what the American commanders did on the morning of January 17, 1991.

After achieving air superiority, coalition pilots were able to fly with almost no restraints, and this was why the air raid sirens never went off until they were switched on manually by our ground personnel. When I explained this to Saddam, he was totally surprised. He said, “You mean we weren’t hit by aircraft?” I said, “No, sir. Not at the beginning.” He had a pencil and paper and he started jotting some notes. Then he looked at me and said, “Okay, then, why shouldn’t we start the artillery barrage now? If we know that aircraft are coming from the south, then we’ll put up a barrage on that side of the city and let them run into a wall of steel.”

I said, “Sir, that’s very dangerous. If you start too early, the batteries may use up all their ammunition before the enemy fighters get there. Furthermore, American fighters

have forward-looking radar and AWACS Sentries overhead that can scan more than 150 miles ahead, and when they detect an artillery barrage in a certain sector they’ll simply turn and go around it. You can’t keep up a barrage forever, and it would be risky to waste our ammunition that way.”

This didn’t make Saddam happy either, and he was getting angrier by the minute. But as we were having this discussion, the telephone in front of us began ringing. I waited to see what Saddam would do, but obviously he wasn’t going to pick up the phone. The air chief should have done it, but Saddam wanted me to answer it. So I picked up the receiver and it was Gen. Ali Hussein, calling from Nasiriyah.

He said, “Who is this?” and I said, “This is Gen. Sada.” He gave me a warm greeting. He was one of my former students as well, when I headed the Operational Conversion Unit. Pilots who had been trained in France, England, or America had to make the conversion to Iraqi equipment and tactics, and Ali Hussein had gone through that school. Now he was a general and commander of a base in the south.

After a very brief exchange, Ali Hussein proceeded to tell me what was happening in the southern sector. I listened to his report, then I looked at Saddam; it was obvious he was hoping for good news. So I said, “Sir, this is Gen. Ali Hussein, and he’s telling me that our air defense missiles have just shot down a British Tornado in the south. They’ve captured both pilots and they’re ready to be processed as prisoners of war.”

Suddenly Saddam’s eyes lit up. He was excited to learn that we were able to bring down an enemy plane. He said, “Is this true? They’ve taken two prisoners of war?” I said, “Yes, sir.” So he said, “What is the Tornado?” And I told him it was a very good fighter built in Europe by German, Italian, and British manufacturers. But then I asked him, “Sir, what do you want me to tell Gen. Ali Hussein to do with the pilots?”

He pushed back slightly and crossed his arms, obviously thinking about what to do next. Then he said, “Okay, here’s what I want to do. We need a man who speaks English very well, who knows the capabilities and tactics of the aircraft, and who knows how to translate those tactics into air defense. He looked at Gen. Muzahim and said, “No, he shouldn’t be the one.” One by one, he checked off a list of all the officers in the headquarters, and finally he turned to me and said, “Georges, you will be responsible for the prisoners of war.”

The Downed Pilots

By Saddam’s command, I was now the officer responsible for coalition pilots shot down over Iraq. So I said, “Okay, sir, I’ll do my best.” When I returned to the phone, I said to Gen. Ali Hussein, “President Saddam has put me in charge of the POWs. So please send them to me right away.” But then I added, “Don’t send them by helicopter or they’ll never make it to Baghdad. Send them by car with some good officers to the air force headquarters.”

The old headquarters building had been bombed and was split down the middle. If it were hit again, it would be a total disaster. So I asked Gen. Ali Hussein to send the POWs to the new headquarters in Baghdad, which was to be located in a large bunker that had been specially built below a civilian bunker. Until now, no one knew that Saddam had built military command bunkers in secure structures below civilian bunkers. It was an act of cowardice contrary to the Geneva Convention to hide military commanders behind women and children. But such things weren’t uncommon for Saddam Hussein.

Anyone who followed the events of that war will recall that the international news media had a field day when American bombers struck the Al-Ameriya bunker, which was full of women and children. Scores of civilians were killed, but this was exactly what Saddam had wanted to happen. If he could somehow persuade the Americans to destroy a civilian target, he would then be able to portray the Americans as aggressors and ruthless killers of women and children, when, in fact, he had built our command posts in the same buildings, beneath public structures.

When the main air headquarters was bombed, Saddam gave orders to move everything—radar equipment, radio communications, and personnel—to the civilian bunker at Al-Maamou, which was in the officer city of Yarmook. The upstairs, as before, was reserved for the use of women and children. But downstairs was the operations center for the Iraqi Air Force, and this, as Saddam knew very well, was against the rules of war. There’s no question that American and coalition surveillance could detect that military communications were coming from that place, and truthfully they would have been within their rights to attack it. But Saddam also knew that, after Al-Ameriya, the Americans were not likely to risk another media disaster.

So I went to that shelter, and that’s where I met with the prisoners of war. It’s also where I continued to work until I was discharged from service and summarily retired once again shortly thereafter. The first prisoner I interviewed, Navy Lieutenant Jeffrey Zaun, had been flying an A-6 Intruder from the Aircraft Carrier Saratoga, anchored in the Red Sea. He was followed by Flight Lieutenants John Peters and John Nichol of the UK, whose British Tornado was shot down. Commander Scott Speicher had been shot down previously, but he died in the crash, and that’s part of a longer investigation I’ll come back to momentarily.

Neither of the British pilots was in very good shape when we got them because they’d ejected at low altitude—less than 150 feet from the ground. Their aircraft took a direct hit from an SAM-3 guided missile. In fact, they didn’t actually eject; they were forcefully ejected by the force of the missile. Their parachutes opened but at such a low level that they hit the ground very hard, and both men suffered trauma and abrasion injuries.

When they arrived and I saw the condition they were in, I called the director of the air force hospital. I told him, “Doctor, I need you to do something for me, and please don’t refuse. I have two guys here, both of them are prisoners of war shot down in the south, and they’re in pretty bad shape.” As soon as I said the words “prisoners of war,” he became defensive and said, “What do you mean, General? I have dozens of patients in here, and more are coming every minute. You expect me to prepare for surgery on two of your prisoners of war?”

So I said, “Look, Doctor. There’s no time for this kind of talk. These are prisoners of war, entitled to all the protections of the Geneva Convention, and I want them alive. So I’m asking you to take care of them just as if they were our own soldiers. Do you understand me?” He knew I meant business, so I immediately had the wounded pilots transferred to a van, and I drove them to the air force hospital myself.

Medical Attention

When we got to the hospital, I went to find Dr. Al-Mukhtar, a military surgeon, an excellent orthopedist, and a general officer in the army. I said, “General, I need for you to give these men the same treatment you’d give an Iraqi pilot. They’re POWs, and according to your religion and mine, as well as the Geneva Convention, you have a duty to give them proper medical attention. And that’s all I’m asking for.”

Dr. Al-Mukhtar is a good man, so he said, “Okay, Georges, I’ll do my best.” Over the next several days he either supervised or performed at least five operations on the men. When they finally went home to England, on March 4, 1991, they were checked out by British surgeons to see if the treatment they’d received was satisfactory. The British doctors said the care they had been given was excellent and nothing more needed to be done.

After treatment, Flight Lieutenant Peters was sent back to the detention center, but Flight Lieutenant Nichol was kept in the hospital for several more days. Whenever I’d go to the hospital to check on him, I could see that he wanted to stay longer. Obviously, he would rather be in a hospital than a prison. When their book, Tornado Down, was published in 1998, telling about that time, the British pilots didn’t have many good things to say about their treatment in the POW camps. But, then, they didn’t say anything very bad either. Obviously, we were at war, and they were strongly against Saddam and the Iraqi military. The good news was that they came out of it alive. Later, Flight Lieutenant John Nichol credited me with saving his life. He was quoted in the London Telegraph as sa

ying, “I’d like to meet Georges and shake his hand.”2

When it came time to prepare my report on Capt. Zuhair’s mission, I learned that Lieutenant Commander Scott Speicher’s F-18 had been hit by an R-40 guided missile. He was hit head on and there was no time for the pilot to react, so Speicher went down with his plane. Several days later, however, the story was circulated that Speicher had ejected and might possibly still be alive. But I’m certain that story was not true. The airplane was completely destroyed, and Speicher did not survive.

We found what was left of his F-18 years later in 1995 with the help of American satellites. We even took a group of American investigators to the site to look for evidence. We examined the wreckage and found the remnants of a flight suit, but no sign of Lieutenant Commander Speicher. Because of the uncertainty involved, the U.S. military changed his status from Killed in Action (KIA) to Missing in Action (MIA). But I believe that was more wishful thinking than anything else.

Several years later, a number of American Christians, whom I had met through my work in the reconciliation movement, came and asked for my help in finding out if Commander Speicher could possibly be alive. I was certain of the facts of this case, but they wanted to check every angle, so I agreed to help. We looked again but found nothing to change my mind. Scott Speicher is dead. There’s no way he could have survived a direct hit from an R-40 missile. That’s a huge weapon, and you don’t walk away from a crash like that.

What did happen, however, was that some Iraqis had taken advantage of the situation for money and even for American citizenship in one case. There was never any possibility that Speicher had survived, but his family and others continued to hold out hope. After the liberation of Iraq in 2003, one of the first delegations to come from America was a group of twelve people looking for Scott Speicher. They called me once again, and once again I agreed to help.

Saddam's Secrets

Saddam's Secrets