- Home

- Georges Hormuz Sada

Saddam's Secrets Page 28

Saddam's Secrets Read online

Page 28

Ironically, more than a year after Junsei Terasawa’s visit to Baghdad, I made an interesting discovery. In another meeting with the Sunni leader, Sheik Abdul Latif al-Hemayem, I happened to mention that Saddam had been given a chance to leave Iraq without penalty. When I told him about the offer of asylum from three Asian countries, he said, “Ah, now I understand!” Then he told me that he had once asked Saddam, “Sir, can we avoid this war?” and Saddam replied, “No. The price is too high.” Sheik Al-Hemayem told me, “I didn’t know then what he meant by that, and I didn’t ask. But now I know what he meant.” The price of giving up control of Iraq, even for a comfortable sanctuary abroad, he said, was more than Saddam was willing to pay.

In October 2005, there was another report that Saddam had agreed to accept an eleventh-hour offer of asylum from the United Arab Emirates, or one of several other Middle Eastern countries. But once again he waited too long and the invasion began before the plans could be finalized. In the end, though, justice was served. Saddam fled Baghdad and his humiliating capture, recorded and broadcast by satellite on December 13, 2003, was an object lesson for the whole world.

The hope I have for Iraq today is that democracy and freedom will come quickly, and that as we mobilize our energies toward greater prosperity and autonomy for all the people, we will be able to avoid tragedies like the ones we experienced under Saddam. It’s my daily prayer that we will have the courage and the foresight to stop tyrants and their bad ideas before they become a problem. Democracy is the best form of “prehap” I know of for doing that, and this is something my people need to understand. We’ve learned some hard lessons in recent years, and somehow we’ve survived. Now we need to be prepared and make sure that no tyrant will ever conquer or mislead us again.

CHAPTER 10

INSURGENCY AND SURVIVAL

Anyone with eyes to see could have seen what was going to happen after liberation. When I realized what was happening, not just the looting, but the pockets of resistance and signs of a growing insurgency, I went to one high-ranking American official, a general officer who was in Iraq on the fourteenth of May 2003, and I said, “General, someone who knows what they’re looking at needs to get involved and help stop the disturbance and disorder that’s going on here.”

He asked me very seriously, “General Sada, can you do this?” I said, “Yes, sir, I can do it. Let me take forty thousand men from the Iraqi Air Force and we will take care of the security of Baghdad, I assure you. Furthermore,” I said, “I don’t need you to give me one rifle, one pistol, one truck, or anything else. The people know us and we know our people. We know our city, and we know where the troublemakers are located. All I need from you is the go-ahead and I will take my forty thousand men from the air force and we will take the city.”

When I told him that, I also said, “When we do this, you can go back to your mission as soldiers. You’ve done a great job here. You’ve won the main battles. The statue has fallen in Fardus Square and Saddam is on the run. So let us finish the job.” He seemed to think my idea made a lot of sense, but when he gave me his answer a few days later, he just said, “Two armies cannot operate in the same war zone.” I asked him, “Why not? If there’s good coordination and cooperation between these two armies to achieve one common aim, why can’t they work together?” But he refused, and that was that.

As a consequence of that decision, the instrument that was used to restore order in the city was totally inappropriate for the task. Tanks, self-propelled cannons, APCs, and mechanized vehicles are great for combat, but they’re not the right tools for restoring security in a large urban center like Baghdad. Anywhere else, I’d want them too; but not in a place like Baghdad.

In the city, those vehicles become perfect targets for those who want to destroy them. And the coalition knew very well that the insurgents and the remaining Baath loyalists had rocket propelled grenades (RPGs), land mines, and rifles, because it was the coalition forces who let them take those things. So when the Americans and the British took over security, it meant that the terrorists would be able to choose the time and place of engagement. They could choose the targets, and they could choose the weapons with which to attack the targets, whether they were tanks, APCs, or platoons of soldiers on foot.

America made the right decision to come in and liberate Iraq, and despite some mistakes, I have to say they’ve done a great job. They broke Saddam’s regime and eventually captured the dictator in his spider hole—that was a tremendous victory, and no one in Iraq or America should miss the symbolism of the way it was done. But the peace is still not won, and the future is uncertain. At the end of a war, there ought to be peace. If there isn’t peace, you’ve done something wrong. Today there’s still fighting in the streets and villages of Iraq, and only time will tell how this war will end.

Supplying the Insurgents

The decision to disband the army was not a bad one, but the way it was done was not very good. What the coalition should have done was to remove the commanders and senior Iraqi officers who had been loyal to Saddam. The first thing they should have done was to activate the law of retirement and, instead of simply disbanding the military, retire high-ranking officers who had been close to the old regime in a more respectful manner. That way these men would have gone away quietly rather than joining the insurgency. There were at that time about five hundred thousand soldiers and officers in the army, and many of them would have been glad to serve under the new command. But rather than keeping those men and getting rid of the Baathis and the Saddam loyalists, the Americans simply disbanded all of them, and as a result, thousands took their weapons and joined the insurgency to fight against America.

It seemed so obvious: the last thing you want to do is to take five hundred thousand trained warriors and turn them loose on the streets with no salary, no pension, no jobs, and nothing to do. Not all members of the Baath Party were bad people. There were four to five million members of the party, and it would be wrong to punish them all indiscriminately. Those who were punished unfairly would be easily persuaded to join the insurgency, and this is a big part of the problem in Iraq today. Besides that, there was no supervision of the ammunition and weapons depots of the army, and they allowed civilians (including many dissidents) to go in and take whatever they wanted—rifles, rockets, anti-tank weapons, and just about everything else. They may as well have said, “Help yourself!” You want RPGs? “Help yourself!” Land mines, C4 explosives, detonating caps, and even surface-to-air missiles were taken by the people.

More than eight million AK-47s had been distributed to the popular army by Saddam, and another four million were stolen from the military arsenals. Just imagine what twelve million Russian-made rifles can do in the hands of people who are angry and disappointed with the way they’ve been treated. Something was very wrong, and this all happened because the victors who liberated Iraq didn’t solve the problem of popular unrest in the first place when they had the chance.

In addition to small arms and conventional weapons, the United Nations inspectors also found a lot of weapons and ammunition that were forbidden during the period between the wars. They destroyed thousands of tons of artillery shells, rockets, and components for building chemical and biological weapons. But I can assure you, they didn’t find everything. Because of his rapid rebuilding capabilities, Saddam managed to hide many of these weapons, along with the raw materials for building weapons of mass destruction (WMDs).

During the times when these weapons were not actually in production— mainly because of the threat posed by the United Nations inspectors—Saddam gave orders that the scientists who had been working on these programs were to keep their plans, diagrams, formulas, raw materials, and everything else in highly secure underground vaults so that they could continue their work the minute they were no longer being observed.

Saddam was committed to using WMDs and he wouldn’t hesitate to use them on his enemies. The level of expertise among scientists who were developing

our nuclear weapons systems was very high, but it was difficult to acquire the specialized equipment that was needed for weapons development. So while he had plans—Saddam had set very ambitious goals for the nuclear engineers—we weren’t as far along in the nuclear program as we were with biological and chemical weapons. But we were very sophisticated with those, and we had plenty of them.

If Saddam ever suspected that there was any chance the inspectors would find something, he would have everything destroyed. But even then, nothing was really destroyed: the scientists had the knowledge and the budget, and when the time was right they would simply begin again. This was even true in the nuclear weapons program. Even though we had not yet developed actual nuclear warheads, we were working on them. We had some components, and Saddam had developed sources in Europe, Asia, and America who were willing to supply whatever we needed.

I learned in 2005 that Saddam had even made arrangements with a group of nuclear scientists in China to produce nuclear arms for him overseas. At least $5 million changed hands at that time, and as late as 1992 these plans were apparently still ongoing. But to my knowledge our own scientists had not yet produced—or acquired by other means—any nuclear warheads that could actually be deployed against an enemy.

An Eyewitness Report

Iraqi engineers were very good at manufacturing chemical weapons systems for artillery shells, rockets, missiles, and other ordnance. By August 2002, Saddam was convinced the Americans were coming; but even then the chemical and mechanical engineers continued building and developing all these systems, on into 2003 and after the American invasion began. Eventually he decided that he would have to gather everything—whether it was complete, partially complete, or only raw material—and take it out of the country, and that’s what he did.

Prior to Operation Iraqi Freedom, no one in Europe or America ever doubted that Saddam possessed weapons of mass destruction. No one could possibly deny that he had used them on many occasions. It’s well known that Saddam ordered chemical weapons to be used against the Kurds at Halabja and Anfal. And there were occasions when the artillery shells and bombs that were used during the Iran-Iraq War were armed with chemical agents.

Before any military operation would begin, the orders given to commanders in the field would tell us when, where, and how to conduct our operations. Within the operations orders there were certain code words that would only be used when air or ground units were supposed to deploy chemical weapons. We never used these code words when conventional weapons were to be deployed. But that’s not the end of the story.

For years now people have been asking what happened to the WMDs. It’s not something that has been widely discussed either in Iraq or America, mainly because of what might happen if these matters were made public. Part of the concern, I believe, is because of where these weapons and materials were taken. Until now, I’ve never spoken about this subject and it hasn’t been made public to the best of my knowledge. I have discussed the subject with officials at the Pentagon, but until now the way these weapons were transported has been a military secret.

Whenever Secretary of State Colin Powell would visit one of our neighboring countries—such as Syria, Jordan, or Saudi Arabia— it’s probable he talked about these things. I don’t know whether he did or not, but there is a tremendous volume of intelligence on these matters, and mountains of anecdotal evidence. These are issues the Americans would likely have pursued diplomatically. But if they did, they have not wanted to make any of that information known to the media or the public.

I am in quite a different situation, however, as a former general officer who not only saw these weapons but witnessed them being used on orders from the air force commanders and the president of the country. Furthermore, I know the names of some of those who were involved in smuggling WMDs out of Iraq in 2002 and 2003. I know the names of officers of the front company, SES, who received the weapons from Saddam. I know how and when they were transported and shipped out of Iraq. And I know how many aircraft were actually used and what types of planes they were, as well as a number of other facts of this nature.

Weapons of Mass Denial

Since none of this information has been made public, there’s been a feeding frenzy in the media for years now, coming particularly from opponents of the Bush administration, claiming that there never were or could have been WMDs in Iraq. This is not true, but I’ve often wondered why this information hasn’t appeared in the media. Why has it been withheld? The Israelis have not hesitated to talk about it. Israel’s intelligence service, the Mossad, is notoriously well informed about military and paramilitary operations in the Middle East, and they’ve said repeatedly that Saddam had weapons of mass destruction. They have also said that some of those weapons were transferred to countries in the region.

The Israeli Army and Air Force have taken military action against arms traffickers and terrorists, and they’ve intervened to stop arms smugglers and drug runners who are implicated in terrorist operations in some of these countries. But the Americans who know what actually happened in Iraq and how Saddam managed to hide these weapons, have not as yet been willing to speak publicly, about the WMDs and what became of them. As a result, those who oppose the war in Iraq have dominated media accounts, claiming they never existed.

When I speak here about weapons of mass destruction, I am referring to the biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons that Saddam had built or was trying to build. Everyone in the international arms community knew that Saddam had them and that he was spending like a sailor to buy more. In a July 2003 interview on CNN, former President Bill Clinton said, “People can quarrel with whether we should have more troops in Afghanistan or internationalize Iraq or whatever, but it is incontestable that on the day I left office, there were unaccounted-for stocks of biological and chemical weapons.”

The White House knew Saddam was armed and dangerous, and the international community knew from past experience that if Saddam had WMDs he would not hesitate to use them—at a time and place of his choosing. Madeline Albright, who was secretary of state during the Clinton administration, said in February 1998, “Iraq is a long way from [here], but what happens there matters a great deal here. For the risks that the leaders of a rogue state will use nuclear, chemical, or biological weapons against us or our allies is the greatest security threat we face.”

Later that same year, Representative Nancy Pelosi, who is now Minority Leader in the United States House of Representatives, said, “Saddam Hussein has been engaged in the development of weapons of mass destruction technology, which is a threat to countries in the region and he has made a mockery of the weapons inspection process.” There are members of the Democratic Party in America who oppose the war today who understood the risks involved in Saddam’s possession of WMDs and said as much at the time. President Clinton’s National Security Adviser, Sandy Berger, warned, “He will use those weapons of mass destruction again, as he has ten times since 1983.” So the fact that WMDs were present was never a secret.

Saddam’s Special Weapons

Everybody understood that reality at the start of the war; I’m convinced it was only politics that made some people change their minds after the fact. But the world has been thinking about WMDs since at least 1990. This was one of the reasons that America and coalition forces decided to invade Iraq in the first place. And that’s why it’s important for me to address some of these things now, to set the record straight.

The point is that when Saddam finally grasped the fact that it was just a matter of time until Iraq would be invaded by American and coalition forces, he knew he would have to take special measures to destroy, hide, or at least disguise his stashes of biological and chemical weapons, along with the laboratories, equipment, and plans associated with nuclear weapons development. But then, much to his good fortune, a natural disaster in neighboring Syria provided the perfect cover story for moving a large number of those things out of the country.

It’s important

to understand, particularly in light of all the controversy of recent months, that Iraq did have weapons of mass destruction both before and after 1991, and I can assure you they were used. They were used on our own people. They were used in artillery shells, cannons, and by aerial dispersion of toxins by both helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft against Saddam’s enemies. And this was always done in a particular way. Whenever we received ops orders to attack using WMDs, the orders never said, “Okay, use WMDs on this one.” Instead they said, “Special mission with special weapons,” and the commanders all knew what that meant.

I’m were recovered later by coalition forces after liberation in 2003, although intelligence officers may not have known what those words, written in Arabic, actually meant. But let me be very clear: in every case, “Special mission with special weapons” meant that the field commanders were to use chemical weapons to attack the enemy.

Large stockpiles of weapons were destroyed by the United Nations weapons inspectors between 1991 and 2003, but I can assure you they never got them all. There were tons of raw material, shells and shell casings, rockets and grenades, both half-completed and fully completed devices hidden in large caches. In 2001 and then again in 2002, Saddam called a meeting of all the top scientists, researchers, and technicians involved in developing weapons systems, and he told them to memorize their plans. Before the paper trail was destroyed linking Saddam to these plans he made certain, on the threat of death and dismemberment, that every single plan and every schematic was committed to memory.

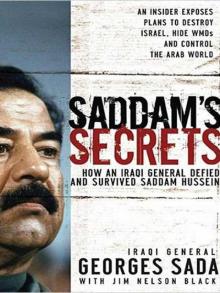

Saddam's Secrets

Saddam's Secrets